Software Project Management

“Deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do. That’s true for companies, and it’s true for products.”

Steve Jobs on the importance of deciding on what not to do

Decision Logs

A decision log is a central register of decisions made on a project. A decision log isn’t for blame. The reason a decision log is crucial is it allows a project team to decide, document and move on. This enables velocity since the team doesn’t need to ruminate on decisions. It’s also handy during team conversations where people feel “déjà vu” and have forgotten what they decided previously as it’s a reference point.

I like the simplest decision log that will possibly work for your context. Ours is a Confluence page with a table in reverse chronological order (so the newest decisions are at the top):

| Question | Decision | Made By / Where | Date |

| Do we want to limit the max records? | We should limit it to 50. That’s a sensible limit and we can adjust based on feedback. | Product owner during Slack Conversation (link) | 28 April 2020 |

A decision log doesn’t mean you can’t change your mind, flexibility is crucial, you just need another decision log entry to show you changed your mind and why 😊

Iterative vs Incremental

What’s the difference between ‘iterative’ and ‘incremental’ software development?

I know a lot of agile software development teams call their blocks of development time ‘iterations’ instead of ‘sprints’. Does that mean they’re doing iterative software development?

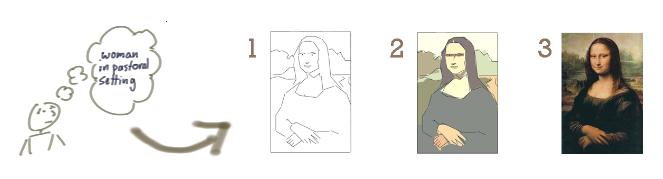

You’ve probably seen the Mona Lisa analogy by Jeff Paton that visually tries to show the difference between the two development approaches:

Incremental Development:

Iterative Development:

But which is better?

Well, if for some (very likely) reason (lack of money, changed business conditions, change in management) we had to stop after iteration/increment one or two, which approach would yield a better outcome?

Incremental development gives us a painting of half a lady whereas iterative development gives us an outline of a lady, but both paintings really wouldn’t belong in The Louvre. Perhaps we could have just painted a smaller painting?

This is where I think the Mona Lisa art analogy falls apart. A work of art, like a book, but unlike a piece of software, has a pretty clear definition of done. An artist knows when their piece of art is done: not a single stroke more, not a single stroke less.

But I’ve never worked on a piece of software that was considered done: there’s always more functionality to add/remove/fix.

If we can recognize that software is never done, all we need to do it work out how to get it to where we want it to be (for now). “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”~ T.S. Eliot

If we are driven by time to market we should internally iterate just enough so we can release ‘increments’ fast and often, and iterate/release again and again.

If we are driven by user experience, we should internally iterate a lot to get things right, release increments only when necessary, and iterate again.

Both approaches are about iterating. Both are also about incrementing. The difference is how soon we release after how many times we iterate.

Compare the beginnings of the two dominant mobile operating systems. Google went for time to market with Android, they released an unpolished, yet feature rich, operating system quickly and made it better by iterating/incrementing again and again over time. Apple took the opposite approach: they released iOS with highly polished features relatively slowly (it took three major iOS releases to get MMS and copy & paste!) but focused on getting things right from the start.

Both approaches are different but neither are wrong: they highlight the differences between Apple and Google and their approach to developing software.

Summary

We can’t build anything without iterating to some degree: no code is written perfectly the second that it is typed or committed. Even if it looks like a company is incrementally building their software: they’re iteratively building it inside.

We can’t release anything without incrementing to some degree: no matter how small a release is, it’s still an incremental change over the last release. Some increments are bigger because they’ve already been internally iterated upon more, some are smaller as they’re less developed and will evolve over time.

So, we develop software iteratively and release incrementally in various sizes over time.

Lightweight Feature Documentation

Example: Royalty Payment Splits

Background

- Royalties need to be paid in full on disbursement to artists.

- A royalty payment can be made to an individual artist, or a group of artists.

- When making payments to an individual artist they get 100% of royalties (no rounding)

- When making payments to a group of artists this needs to be split by the percentage splits defined in the system which always add to 100%

- When splitting a payment across a group of artists and it doesn’t split evenly into cents, the system currently randomly splits the cents between artists to balance out the rounding over time

- This causes issues for both automated tests which need deterministic behaviour, and artists who are confused why they get slightly different amounts if their royalties are the same.

Scenarios / Examples

| Scenario | Royalties Owed | Current Royalties Paid | New Royalties Paid | Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single artist gets 100% of whole payments | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | ✅ |

| Single artist gets 100% of payments including cents | $66.67 | $66.67 | $66.67 | ✅ |

| Two artists with 50% each for a payment that can be split evenly | $100.00 | artist 1: $50.00, artist 2: $50.00 | $50.00 | ✅ |

| Two artists with 50% each for a payment that can’t be split evenly | $100.01 | $50.01 $50.00 is randomly assigned to artist1/artist2 | artist 1 $50.01, artist 2 $50.00 | ❌ |

| Two artists with 50% each for a payment that can be rounded to ten cents – no rounding | $100.30 | artist 1: $50.15, artist 2: $50.30 | artist 1: $50.15 artist 2: $50.30 | ✅ |

| Three artists with third splits can’t be split | $100.00 | amounts of $33.33, $33.33 and $33.34 randomly assigned to group members | artist 1: $33.34, artist 2: $33.33, artist 3: $33.33 | ❌ |

| Three artists with third splits can’t be split – more than a single cent difference | $100.00 | amounts of $33.33, $33.34 and $33.34 randomly assigned to group members | artist 1: $33.34, artist 2: $33.34\, artist 3: $33.33 | ❌ |

Business Rules

- Royalties need to be paid in full on disbursement to artists.

- A single artist gets a whole payment.

- When payments can be split evenly to a group of artists (to the cent) they are split that way.

- When payments can’t be split evenly to a group of artists, the payments are split into an even split and the remaining cents are distributed to the members in whole cents.

- The first member in the group – based on earliest date/time added to group – gets the higher amount, followed by the second, third etc. based on earliest date/time added.

- Payments aren’t rounded to ten cents or five cent amounts, only whole cents

Questions/Decisions

| Question | Decision | Made By |

|---|---|---|

| Do we want to round to five or ten cent distributions? | No, we’ll always round to the cent | Product Owner via Slack # |

| How do we distribute based on membership of group? | We’ll use the date time added to the group (first gets most) | Team during kick off meeting |

Prioritisation: Now, Next, Later, Never

Our team sets quarterly objectives, which we break down into requirements spread across fortnightly sprints. As the paradev on my team I work closely with our product owner to write and prioritise these requirements.

We originally started using the MoSCoW method to prioritize our requirements:

The term MoSCoW itself is an acronym derived from the first letter of each of four prioritization categories (Must have, Should have, Could have, and Won’t have

We quickly started noticing that the terminology (Must have, Should have, Could have, Won’t have) didn’t really work well in our context and how we were thinking, and this caused a lot of friction in how we were prioritizing, and adoption by the team. It didn’t feel natural to classify things as must, should, could, won’t as it didn’t directly correlate into what we should be working on.

Over a few sessions we came up with our own groupings for our requirements based upon when we would like to see them in our product: Now, Next, Later, Never. We’ve continued to use these four terms and we’ve found they have been very well adopted by the team as it’s very natural for us to think in these groupings.

The biggest benefit of using Now, Next, Later, Never is they naturally translate into our product roadmap and sprint planning.

I did some research in writing this post and found Now, Next, Later as a thing from ThoughtWorks back in 2012, but I couldn’t find any links that included the Never grouping as well which we’ve found very useful to call out what we agree that we won’t be doing.

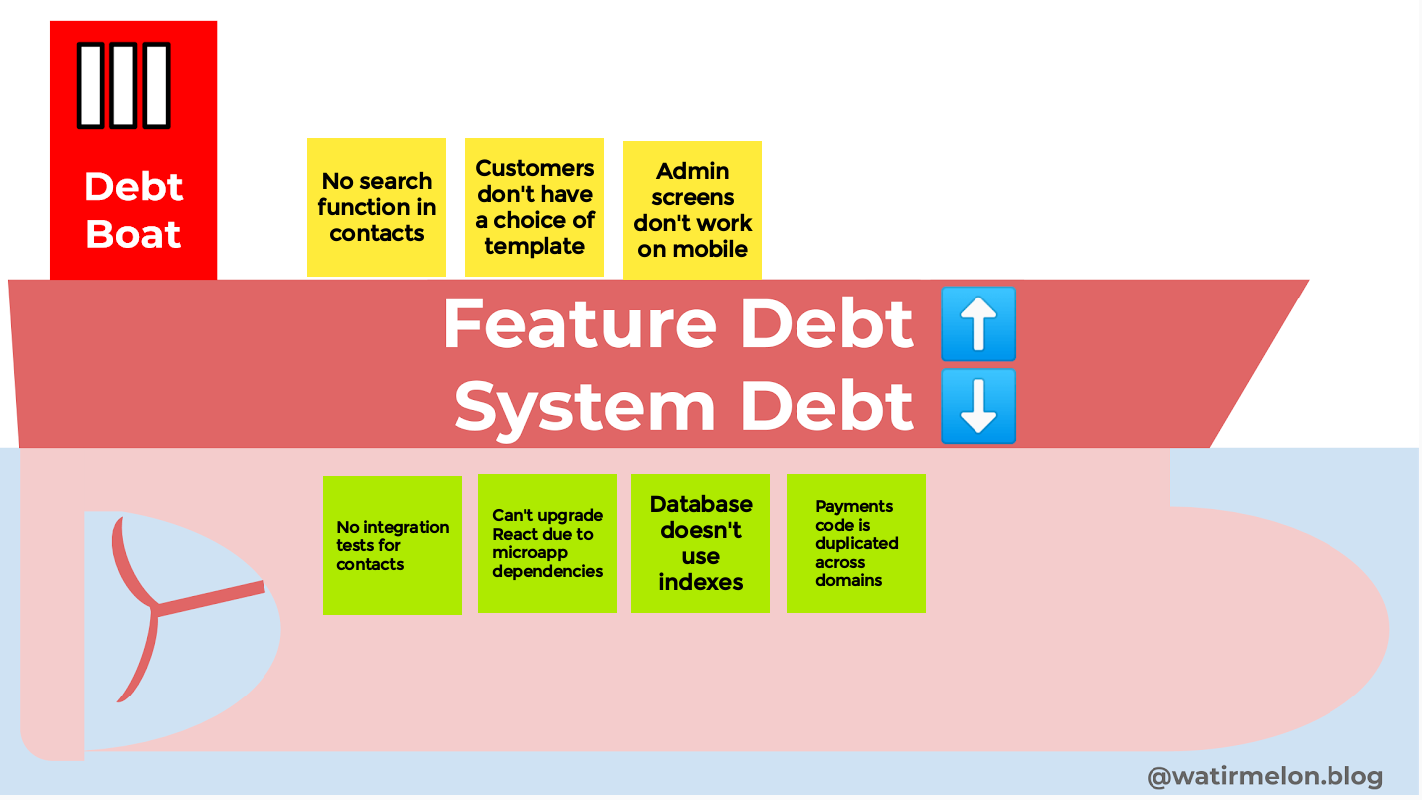

Visualising Technical Debt (with the Debt Boat)

Being successful in software delivery requires a team to constantly balance technical debt and feature delivery. Teams often fall into the trap of delivering features too rapidly at the expense of ever increasing technical debt, or delivering a over-engineered solution at the expense of not delivering things within reasonable time-frames and before any real world usage.

This is one of the key issues facing most software delivery teams I have worked on as there are often different appetites for delivery vs debt throughout an organisation.

I was trying to come up with a way to present technical debt in a visual format that could be easily understood by different people: management, stakeholders and a development team.

One thing we value is shipping things: getting our products in the hands of customers so they can get value from them. Accumulating technical debt, both customer facing and “under the covers” may allow us to rapidly get features to our customers, but eventually the debt grows and affects our ability to deliver.

In the “shipping” theme I came up with the Debt Boat: a way to visually represent things that build up and eventually slow us down. I like splitting technical debt into both feature debt: things our customers want but we chose not to do, and system debt which is technical things our customers (or product owners) can’t see (below the water line) but increasingly slow us down.

We originally had this boat on our team’s physical wall to show there’s only so much technical debt we can take “on board” before we sink.